Short embarking upon a personal journey down a thousand foot shaft into a hollow of active mine galleries, seven hundred and fifty miles of mining tunnels creates a subterranean world that beguiles the imagination and confounds any just attempt to truly conjure its nature. As grand excavation, there are few handiworks of mankind that lie so completely hidden from view. And there are few environments men can create that are so hostile. The will to drill into the earth is mankind at his most invasive and determined. A labyrinthine monster is created- one half of the creature a newly created atmosphere and the other the sum total of forces once buried deep within the bedrock now partially unearthed. Poke holes into the earth’s crust and both the air we breathe and the gases the earth exhumes rush in to fill what would otherwise be a vacuum which nature abhors.

Like the innards of a snake, the gas-air mix becomes the stuffing of a mine’s hollow body, and as would any reptilian creature takes on the heat that surrounds it. The planet’s crucible is the earth’s molten core, and its invisible tentacles of heat radiate out through the earth’s body in search of the surface, seeping their way through mantle and then bedrock. Blast a hole in that egg shell of stone and in capillary reaction waves of infra- read accompanied by moisture and noxious gases rush in all the faster. Drill a little deeper and the heat becomes unbearable and filled with poisonous gases that kill on contact.

And all this in a search of those precious metals that appeal simultaneously to our most base and refined aesthetic instincts.

The following is taken from the book The Big Bonanza published in 1876 by the reporter and mining expert, Dan DeQuille, who worked for Virginia City’s fabled newspaper, The Territorial Enterprise. (The Enterprise also employed a young reporter by the name of Mark Twain, who coincidentally helped DeQuille get the book published years after Twain left Virginia City). It graphically depicts the hellish environment of an aging Virginia City mine:

“Some of the old shafts opened on and about the first or upper line of bonanzas have quite gone to decay. They still stand, but the timbers in many places, far down in the bowels of the earth, are racked and rotten; while the timbers built up in the mine to support the chambers from which ore was extracted, and set up in the galleries, drifts, crosscuts, and chutes, millions on millions of feet in all, have quite gone to decay. It is perilous to undertake the exploration of these old worked-out levels. In many places they are caved-in in every direction, the old floors are rotten, water drips from above, and a hot, musty atmosphere almost stifles the explorer; in places the air is so foul that his candle is almost extinguished.

Down in these deserted and dreary old levels, hundreds of feet beneath the surface, are encountered fungi of monstrous growth and most uncouth and uncanny form. They cover the old posts in great moist, dew-distilling masses, and depend from the timbers overhead in broad slimy curtains, or hang down like long squirming serpents or the twisted horns of the ram. Some of these take most fantastic shapes, almost exactly counterfeiting things seen on the surface. Specimens of these are to be seen in most of the cabinets of curiosities in Virginia City. Some of the fungi that

grow up from the bottoms of old disused drifts are wholly mineral and are composed of minute crystals of such salts as are contained in the earth from which they spring.

These old decaying places breed all manner of gases, some of them, as the firedamp (carburetted hydrogen gas), dangerous to human life.”

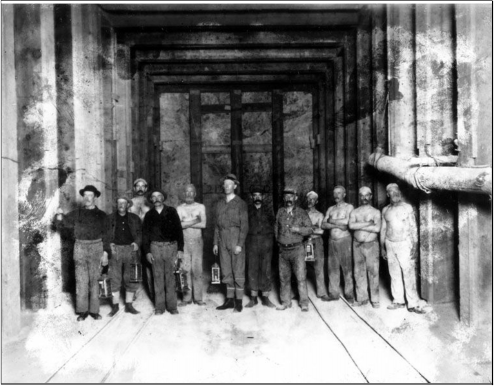

Seven hundred and fifty miles of mines excavated in an explosive fury of human activity over thirty year’s time- from 1859 to 1890- this is the archaeological legacy of Virginia City, Nevada. Its famed Comstock Lode produced so much wealth that some claim it financed the Civil War (for the Union Blue if you’re wondering). Due to the great extrusions of silver bullion from Virginia City’s deep-lode mines President Lincoln put the Nevada Territory on the fast track to becoming a state. More locally, some of the handful of men who became richest off the mines used that money to develop San Francisco into a major world city.

Virginia City’s Ophir mine installed the first steam hoisting machinery on the Comstock in 1860. The mine was worked through an inclined shaft which followed the drift of the ore vein. A track was laid down the incline. A fifteen horsepower donkey engine raised and lowered a car on the track. Draining the mine was accomplished with a small pump,

and keeping the mine dry even at one hundred eighty feet which the Ophir reached in December of 1860 was no small feat. The veins of ore were so deep and wide that the standard practice of using posts and caps to hold up the roofs of the tunnels and caverns was ineffective. How was it that several mining operations could extract silver ore from a vein eighty feet wide, over a thousand feet deep and two miles long? The Comstock Lode was a bonanza the geological likes of which the world hadn’t ever seen. Excavation techniques could carve out huge caverns to expose the veins, but keeping the caverns from caving in became a monumental problem that threatened the whole enterprise. Desperate mine owners called in a German mining engineer named Mr. Philip Deidescheimer to save their interests. As a graduate of the Freiberg School of Mines in Germany, he had been educated at the world’s foremost institute of mining technology. Deidescheimer spent a few weeks on location before devising a new system for supporting the walls and ceilings of Virginia City’s increasingly unstable mines. Though his invention single handedly saved the economy of Virginia City, Deidescheimer received next to no monetary reward for his contribution.

Referred to as square set timbering, hollow cribs of heavy set framed timber were stacked one on top of another as a support between the roof and floor of a mine. If the veins of ore were wide enough, a number of these cribs were backfilled with waste rock forming pillars of stone reaching up to the roof of the mine. The yielding characteristic of the wooden frames gave equal support to the walls, floors, and roofs of the mine shafts and drifts. The size of a man, the beams were twelve-to-eighteen inches square and joined in a mortise and tenon system. The pressure upon the cribs was so great than the original eighteen inches would sometimes be compressed down to two or three. It became as solid as iron and as difficult to cut.

Without this innovation the Comstock Lode would have come to a screeching halt. But it was not a problem-free technology. Even though the compressed cribs were nearly as strong as steel, their installation was far from permanent. Deep lode mining is always accompanied by table water leeching into the drifts and galleries. Sump pumps were at work around the clock to export water collecting in pools in the galleries, drifts and at the

bottom of the mines on up through hoses and out of the shaft entrances or vents. Floods occurred with regularity anyway, inundating the cribs. As bathed in constant humidity and high atmospheric temperatures, they soon rotted. All the owners could do was tear down the cribs and replace them. The need for milled lumber was never ending.

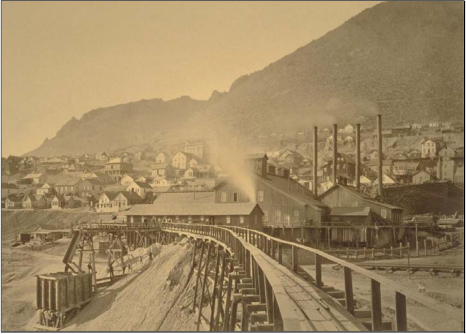

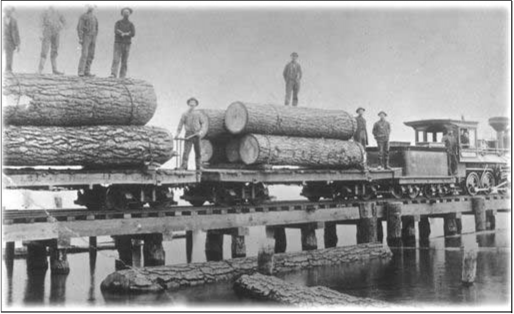

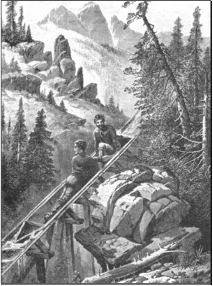

The owners called far and wide for timber to be logged and milled. Virginia City stood at the foot of arid Mount Davidson on the edge of the Great Basin in the middle of dry desert sage. There were few stands of timber in the surrounding area. Any useable wood products found in the nearby Pine Nut Hills were soon exhausted. The timber would have to come from far off in the Sierra Nevada. Timbering the mines resulted in lumber companies springing up throughout the eastern Sierra Nevadas and over into the Lake Tahoe Basin. Soon, stand clear or strip lumbering took a huge toll on the natural environment. Lumber jacks stripped the hills of trees for stretches of hundreds of miles and fed almost all of it into Virginia City’s seven hundred and fifty miles of mines. The ravenous Comstock consumed upwards of 80,000,000 board feet of lumber a year. One of the larger mines alone fed on 6,000,000 board feet in a single year. To this day, the eastern slope of the Sierras vividly shows the scars of a quarter-century of strip lumbering.

Lumber mills were often built on site where the great trees were felled. Many of the trees, most of them species of pine such as Ponderosa, Jeffrey, and Sugar Pine, were milled to specification for square set cribs. Still there remained the problem of transportation. Railroads were built, but often the lumber was felled and milled in mountainous areas far removed from the Great Basin valleys below where the only tracks had been laid.

A few enterprising men set their minds to tackling this logistical problem. One of the better positioned and more energetic was D.L. Bliss, an immigrant from Scotland. He founded possibly the largest lumber operation that fed the great maw of the Virginia City mines. His company, the Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company, was put into operation in 1873 in Glenbrook. Glenbrook was situated on the east shore of magnificent Lake Tahoe, which occupied a deep granite graben between two rifts high in the sky just beyond the eastern escarpment of the Sierras above the Carson Valley. When CTLFC’s operations were put into high gear, Tahoe’s great virgin forests ringing the lake’s seventy-two miles of shoreline were still nearly untouched. Not only did Glenbrook’s mills feed off the timberlands Bliss had rights to on the lake’s east shore, but Bliss employed the steamboat Meteor to tug rafts of logs over from across the lake as lumbered on other land holdings he owned on Tahoe’s south and west shores as well. Loggers brought cut timber to the lake via flumes or greased skids or cattle drawn operations. On the South Shore in Bijou for instance, the logs were loaded off an 1800 foot pier into the lake and confined into V-shaped booms consisting of a number of long, thin poles fastened together at the ends with chains. The Meteor could tug rafts containing up to 350,000 board feet of lumber. Once they reached Glenbrook, the logs were hoisted onto saw carriages and rolled to the waiting mills.

The heavily wooded ridge that rose steeply to the east of Glenbrook crested more than a thousand feet above the lake. At the top of Tahoe’s eastern basin ridge a great escarpment plunges down a few thousand vertical feet into the Carson Valley below. Messrs. Bliss and partner Yerington, CTLFC’s co-founders, built a narrow gauge railroad

that hauled the wood up to the ridge at Spooner’s Summit, some six miles from the mills below in Glenbrook.

On that ridge, a second important invention was introduced that made the Virginia City mines an economically feasible enterprise. In the Carson Valley below lived a James Haines, resident of Nevada’s first white settlement, Genoa. He solved the impasse of delivering lumber from the Tahoe Basin down into the Carson Valley by designing the first V-shaped flume. (A flume is a watercourse that consists of an open artificial chute filled with water for power or for carrying logs) Each flume section consisted of two boards, each two feet wide, one and one-half inches thick and sixteen feet long, joined at right angles. Each section underlapped the one above it and iron ribbons were used to strap the boards together. The entire structure was upheld by props resting on the ground. In order to cross ravines, trestles were used.

Yerington and Bliss’ first of many flumes was twelve miles long and snaked its way from Spooner’s Summit down Clear Creek Canyon to the Carson Valley; its terminus meeting up with the Virginia & Truckee Railroad. It had a capacity to carry 500,000 board feet of milled lumber a day. In order the keep the flume full of water, Bliss damned a watershed a few miles north of Glenbrook and created a large reservoir called Marlette Lake. Into

the flume a constant stream of water was poured from Marlette and other reservoirs which during the logging season carried upon its bosom a stream of boards, timber, studding, joists and sheathing. At its peak of Glenbrook’s operation, the CTLFC holdings included 50,000 acres of timber at Lake Tahoe and Lake Valley (some bought for $1.25 an acre), three mills at Glenbrook, two steamers two logging railroads, logging camps, and a narrow gauge railroad. It operated several flumes to transport lumber down the mountain to the railroad depots and also maintained a box factory in Carson City. The company would buy large plots of land cheaply from people who would acquire land from the government in some of the land giveaways that were going on at the time.

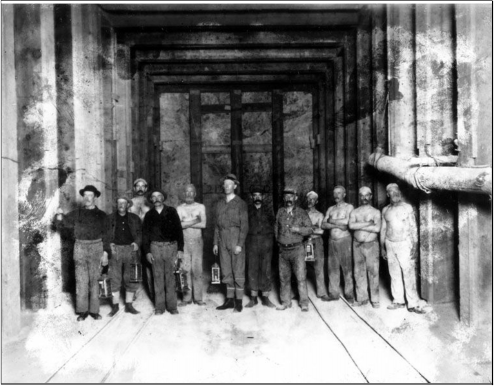

The invention and implementation of square-set timbering and V-shaped flumes transformed Virginia City’s initial pick and shovel mining into a major industrial enterprise. In the turn to industrial mining, many prospectors became hourly wage earners, stripped to the waist to work in the underground tunnels of such mines as the Ophir, Yellow Jacket and Crown Point. Beneath the surface hundreds were killed, maimed, or seriously injured. There were periods when a man was killed every week by cave-ins or fires and a man injured every day by falling into shafts or sumps of hot water.

Working 2,000 feet underground brought severe occupational hazards - heat exhaustion, pneumonia, silicosis (miner's lung) and rheumatism. Heat increased five degrees Fahrenheit every hundred feet. At 3,000 feet, clouds of steam obscured a man's work, wooden pick handles became so hot that miners had to use gloves, work time was reduced to fifteen minutes out of each hour, and the ice allotment went up to ninety-five pounds a day per man. Fire, explosions, cave-ins, poisonous gas, falls into shafts, or falling into sumps of hot water- these were all major causes of mining deaths and injuries. During its peak industrialized production years of 1863-1880, Virginia City’s Comstock Lode boasted one of the world’s worst industrial accident rates.

The miners may have suffered greatly, but this hearty stock measured their manliness according to the gamble they undertook working in the mines. Without that gamble, the adventure may have not even been worth their time. The gold digger who put everything

on the line as an independent prospector could pride himself on the fact he had taken the venture on himself, come success or failure.

In a strange twist of fate, the industrialization of the Virginia City mines turned the thousands of miners working there into salaried employees whose earnings topped-out at about four dollars a day, whether the mine owners were making money or not. This transformed the American myth of seeking out one’s fortune independently into a much tamer, more “civilized” one where a man’s wages were paid by investment capital. He suddenly had been transformed himself from a free, risk-taking adventurer looking to strike it rich into a mere laborer for hire working for a capitalist boss.

This dynamic change didn’t drive many of the miners away, though. In fact, they mobilized in solidarity to look after their collective interests and quickly became unionized; funding their own medical and death benefits through union dues and their leadership negotiated with mine owners for higher wages. Unions and mine owners not withstanding, miners still lived according to a carefully calculated code of risk. Guaranteed wages did not erase the dangers miners faced. The manly gambles that miners assumed both below ground in the mines and above ground in the city’s gambling saloons were often denounced by Virginia City’s middle-class as embodied by its merchants, doctors, those in the legal profession, and stock brokers. But the miner’s risk- taking behavior was crucial to their self-identification. Such pride was characterized by independent strength- both mental and physical- and a political militancy that stood up against the capitalist class and foreign races that competed for their jobs. These attributes culturally defined working-class manhood in Nevada. Such risks fundamentally distinguished miners from their middle-class fraternal brothers. The miner’s working- class notions of acceptable risk included the provision that they had the right to protect their interests, limiting their risk. It rationalized their position of excluding non-white workers from their ranks (such as the detested Chinese who competed for available jobs) or to support the manly gamble of a charismatic capitalist such as John Sutro.

Due to its larger-than-life nature Virginia City would have been difficult to be rendered according to Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory, but it was still a setting that the writer could have easily exploited as literary grist to be included in his book of short stories, Men Without Women. Most of Nevada mining towns- all of which followed a boom-and-bust pattern of short term existence- were much the same in demographic character. Though some families eventually established themselves in places like Virginia City, the overwhelming percentage of inhabitants in the boom years were male; most of them young and unmarried miners. Especially in the city’s early years, most of its female residents were prostitutes, the most historically celebrated of the “soiled doves” being the much-written-about Lady Julia Bulette. Her tenure in the heart of the city’s commercial district was a short-lived four years as she was brutally robbed and murdered in her two- room crib near the corner of D and Union streets in 1867. An excerpt from Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise’s report on her murder touted Miss Bulette’s civic pride and “participatory philanthropy”:

“Julia Bulette was some time since elected honorary member of Virginia Engine Company No 1, of this city, in return for numerous favors and munificent gifts bestowed by her upon the company; she taking always the greatest imaginable interest in all matters connected with the Fire Department, even on many occasions at fires working at the brakes of the engines. She was still an honorary member of the company at the time of her death; therefore it was proper that she should be buried by the company.”

As the white man’s culture of Nevada in the late 19th century was culturally evolving along schisms of class, gender, and race, it also made short shrift of the indigenous Native American population in order to set the stage for such self-determinations.

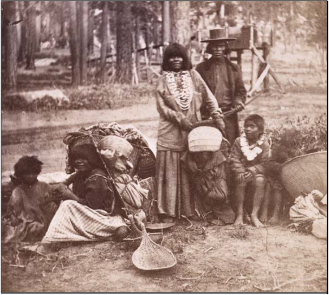

The white man’s harnessing of those natural resources as found in Virginia City, the Carson Valley, and Lake Tahoe doomed the tranquil lifestyle of the indigenous peoples who had populated the area for millennia. Most of the onus fell on the backs of the Washoe Indians. The small tribe once claimed Lake Tahoe [suggested origins: da-aw-a- ga-a or Camp on the Shore; or 'Tache' (Much Water) plus 'Dao' (Deep or Blue Water)] as the very heart of their territory. Beginning in 1860, they lost access to important traditional areas on the lake’s east and west shores to the Comstock logging and lumber operations and the accompanying environmental degradation. The first white men to descend upon the lake simply claimed squatter’s rights to the land. The Washoe Tribe was denied any claim to the lake, and Washoe tribal members became guests in their own territory.

Among the sites lost to the Washoe was Cave Rock, a towering three hundred foot rock buttress situated flush on Lake Tahoe’s southeast shoreline. A remnant of an ancient volcano, Cave Rock is still considered by modern day Washoes the domain of powerful spirits, and it is so sacred that only a few elders are allowed to visit it. To this day there is disagreement between the modern Washoe and organized recreations groups (specifically rock climbers) as to proper use of Cave Rock.

![]()

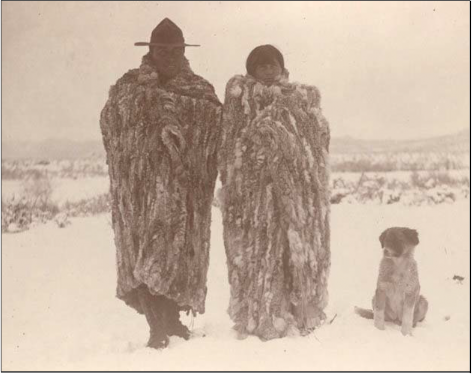

A hunting and gathering tribe that lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle, the Washoe lived in the Carson (or Washoe) Valley area during the winter months. During this season when the Sierra Nevada were covered in snow, some of their diet consisted of fish as caught in area’s rivers and lakes, but the bulk of seasonal sustenance was derived from pine nuts, roots, and berries they gathered in the semi-arid, high altitude desert. The pine nut was their staff of life, and most of the pinyon nut trees were to be found clustered in the Pine Nut Hills growing along side Juniper berry trees and various types of sage. The pinyon tree hills were teaming with rabbits, which the Washoe hunted not only for their meat, but for their hides. The Washoe sewed the hides together to made fur garments that served both as coats and blankets. Though the Carson Valley received little snow fall, its winters were often colder than what was experienced in the Lake Tahoe basin.

The rugged terrain and relative lack of big game in the Carson Valley restricted the movement of the Washoes. Though they did some hunting of deer at Tahoe during the summer and antelope and rabbit in the Carson Valley, their diet of meat came more from fishing than the hunting of game. Wild game populations were not profuse in their wintering grounds. Their survival during the winter months was almost wholly dependent on the bountifulness of the pine nut crop. During the short gathering season, one family could gather upwards to fifty pound of nuts a day, and the total amount they gathered determined whether the winter would be characterized by reasonable food stocks or semi- starvation. Economic dependence was based within and satisfied by family cooperation. Tribal villages descended upon good pinyon tree clusters and worked together, but each family was responsible for garnering its own winter stores of food.

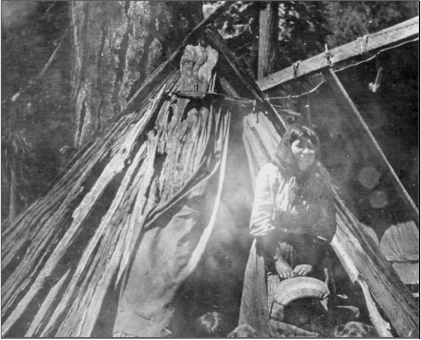

Once spring thawed and the snows abated from the mountain passes, the tribe would walk overland out of the Carson Valley and cross the Sierra’s eastern escarpment, making their annual migration to their spiritual home of Lake Tahoe. They spent a great deal of their time fishing the spawning grounds found in the multitude of streams that fed the great lake. Women collected reeds and bark in order to make the now famous basketry that some say are the finest examples found amongst any North American tribe. They would return to their ready-made dwellings they had left behind the previous fall, and

make necessary repairs. Their conical-shaped dwellings consisted of bark and plank slabs stacked on top of a leaning pole structure tied together at the top.

Archaeological reports vary, but the Lake Tahoe region encountered by early settlers had been subject to Washoe land use for at least 1,300 years. Some say the tribe had occupied their greater area of occupation just east of Lake Tahoe for 9,000 or more years.

The early settlers viewed the undeveloped Indian lands they first laid eyes on asn“neglected.” They believed the Washoes as well as most other tribes practiced a form of land management that created a “natural, unimproved, and un-owned landscaped.” Lacking agriculture per se, the Washoe were perceived as passive in their relationship with the environment. The great land grab that more than any single dynamic defined westward expansion had a firm basis of rationale. Aside from broader concepts such as Manifest Destiny and overt racial superiority, American pioneers, businessmen, and politicians felt justified in taking land from primitive peoples whose cultures were often based on nomadic ways and lack of private ownership. In fact, many didn’t believe they were taking land away from the Indians at all. How can one take land and resources away from a people that never “owned” them to begin with? The pioneers brought with them much more than covered wagons, horses, and their dreams of establishing a new life. It was their cultural mind set more than any single factor that determined their behavior towards the land and its original inhabitants. The more complex social and economic habits of white people necessitated they exploit the resources of whatever land they occupied. As Indians were considered sub-human by many whites made it all the easier to wrest the land away from them. If the indigenous peoples provided resistance, they were simply killed off. In stunning contrast, the Washoe were a people whose needs were simple and political organization comparatively nil. Their numbers were extremely small, land base large, and they spread out into many politically and economically independent villages. Each had a village chief and hunt-chief, but their authority was limited as real power resided within each family as applied to only those members of the family. The chief ruled in a fatherly fashion, and did not hold a burdensome canon of tribal law over the heads of the few tribal members that constituted a village population. The leadership role was akin to that of an admired advisor or spokesperson. Generosity, humility, and wise counsel were expected of leaders or the group would reject them and turn to another. The hunt-chief held an important position, and wielded an unusual amount of say as he dictated when and where hunting could be held. But he could retain his position based only upon demonstrated competence as best served the needs of the entire community. Village autonomy was respected and ties between communities were voluntary. Headsmen or headswomen could forge cooperative alliances with other villages for purposes of producing festivals, participating in game drives or provide for a common defense, but such relationships were purely voluntary. As it stood in aboriginal times, the encumbrances of Washoe political rule were minimal. Authoritarian rule was foreign to the tribe. Good will was the tribal basis of cooperation. Most striking was that the Washoes were an egalitarian society who through group recognition awarded positions of leadership or special skill to those who demonstrated the desired ability. This system of meritocracy applied to women as well, and they often assumed important positions in Washoe life including that of village chief. Social distinctions according to wealth and status did not exist. The need for social organization was more expressed in communal acts such as banding together to fish and hunt or celebrate a handful of religious rituals. Other special rites of passage took place at the birth of a child, boy's puberty, girl’s puberty, marriage, and death. Direct appeals to nature came in the form of the Jack-Rabbit Dance, Acorn, and Pine Nut Dances. The Washoe had a rich tradition of story telling and a complex creation myth. They were animists and believed the forces of nature need be propitiated. Animals were personified in myth, all natural phenomena was considered sentient, and spirits of the dead were feared. In aboriginal societies, animism and worship of ancestors often go hand in hand, but Washoe religion was not characterized by ancestor worship. Their genealogical reckoning was very shallow. The Washoe were not attached to their ancestry within a basis of clan history, either. In fact, clans did not exist among the Washoes, and totemic names were unknown. For example, the name given to a child was derived from the infant’s mispronunciation of a word and was never deliberately changed. The Washoe extended respect of the individual to all its tribal members beyond their immediate associations of family or village. This value was offered to neighboring tribes as well. From what can be gathered, the Washoe have no history of demonstrating willful aggression against the neighboring Paiute, Miwok, or Maidu tribes. They would respond violently to aggressive intrusion or violation of their lands or food supplies, but were not motivated to expand their own territories or lord power over others. No Native American Indian tribe ever successfully stood up to Westward expansion. Almost all were either annihilated or at the very least displaced from their traditional homes and forced to relocate to U.S. Government approved reservations. The land was often not arable and bone dry. The practice of agriculture was often impossible. Though the Washoe were able to physically survive as they offered no resistance to the white intruders, they suffered more handily than did a lot of tribes, as they initially were incapable of doing their own bidding and were not awarded any reservation land until 1934. But the government compensation for redevelopment that was vital to any real hopes of tribal revitalization was not forthcoming until 1970. As forcefully displaced from both their summer and winter residential and feeding grounds, the Washoe were set adrift from the late 1850’s until funds finally became available to them in 1970. Given their peaceful nature and small numbers, they found no other possibility to survive during the interim other than to languish in servitude working in positions of a menial nature within white communities at Lake Tahoe and in the Carson Valley. They were sometimes confined to life within mixed Indian colonies, something they hadn’t ever experienced. The common afflictions that beset a vanquished people were visited upon the tribe during that one hundred twenty year period. Mental depression, alcoholism, and loss of cultural identification began to take hold. There has been a remarkable turn around for the tribe since the watershed year of 1970. With the five million dollars they finally received from the U.S. Government (which was only a small part of the forty-three million promised them in 1948), they invested wisely and quickly moved forward to recreate tribal organization and the overall well being of their people. They have reestablished their cultural identity and promoted themselves with great success. Having finally learned how to deal with U.S. government agencies and adapt to American community standards, the Washoe have organized according to modern modes of survival and in the process have not only elevated their standard of living, health, and education phenomenally, but have worked hard to rescue their cultural traditions as well. The destructive legacy of Virginia City’s industrialized mining in the last half of the nineteenth century has turned out not to be the death knell for the Washoe. On the other hand, the other major victim- the environment- is still a ravished entity whose recovery has only been partial. Moreover, its future health is very much in question. Fire. In a word, it is fire that could now wipe out what forests were able to regenerate after the whole scale stand clear logging that virtually destroyed millions of acres in the surrounding hundreds of square miles that supported the endless hunger for timber demanded by the Virginia City mines. The USDA Forest Service is just one governmental agency grappling with the ill-effects of the clear-cut logging that denuded much of the Tahoe Basin, most of the damage taking place between 1860 and 1890. Tahoe’s surrounding mountainsides- amounting to some 165,000 acres- were originally cloaked with open Ponderosa pine woodlands maintained by frequent low-severity fires. After the big pines were logged to provide timber for mines and railroads, foresters maintained a strict policy of suppressing fire whenever possible. Their efforts were largely successful. When timber land is clear cut, the forests that grew back do not resemble those as found in their virgin condition. In the case of the Tahoe Basin’s original Ponderosa forests (which included fire resistant Sugar pine and Jeffrey pine species), their reforestation was dominated by dense stands of fast growing white fir, which grew in compact clusters. The forests are now choked with a density of trees that is at a 10,000 year high. White fir is susceptible to both drought and insect attack. Subsequently, many have died off in alarming numbers, much of the mass- killing due to beetle infestation. In forest lands across America, many Native American tribes historically understood the role fire played in the life of forests, and learned how to manage the natural force properly so that catastrophic forest fires did not break out. They were active stewards of the land, and employed controlled burns in order to reduce forest floor fuel loads. The Washoe Indians practiced such techniques in the Tahoe Basin and the result was the preservation of Tahoe’s big trees. This not only prevented outbreaks of dangerous-sized fires, but also opened up the forest, making it easier trek across the countryside as well as to follow and hunt game. Modern foresters are now clearly aware and in general supportive of these Native American forest management techniques. They have also adapted some of those techniques as part of their general scheme of preventing severe fires. Simply put, one controls fire by using fire. Outright suppression of all fires it has been painfully learned is a failed policy. In pre-settlement times much of the Tahoe Basin burned every five to eighteen years. Such rates have dropped to near zero now. Forest fuel loads have increased several magnitudes. Man must now interject a compensatory hand following the overturning of nature’s rhythms beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. In such an effort, controlled burns and attempts to collect and recycle undergrowth which is converted into bio-mass fuels are becoming increasingly common practices by all manner of fire agencies. This is especially true since 1988 when the catastrophic fire in Yellowstone destroyed 40% of the park. But in the Tahoe Basin, it appears catastrophe looms as a prolonged debate over how to deal with the huge number of dead and dying trees densely cloaking the entire surrounding region rages on. Many environmentalists decry the cutting down of any trees or forest thinning of any kind, especially in the wet areas or so-called “stream- environment zones.” They fear the effects will cause erosion, clogging the local streams and wetlands with sediment which will introduce more nutrients into the lake and further degrade the already diminishing clarity of Tahoe’s fabled crystalline waters. The foresters who are actively reducing forest floor fuel loads at present counter that a massive fire will dump tons of burning ash and smoke particulate into the lake, polluting it much more severely. It is agreed that given a specific set of conducive environmental conditions- especially one where dry, persistent winds prevail- an errant lightening strike (which is pervasive in the Sierra Nevada), abandoned campfire, careless thrown cigarette butt, or arson’s match could cause an apocalyptic fire in the Tahoe Basin. As almost a third of the basin’s trees are dead and dried-out, it is not an exaggeration to imagine the occurrence of a fire storm. Evidence of the extreme danger is already in. The Gondola fire of 2002 on the lake’s South Shore could have easily burned out most of the surrounding communities if it hadn’t been for a fortuitous shift in wind. But even without the beetle infestation, dense forests of healthy trees could be considered of even great potential danger. The oils, resins and sap in the needles and fine branches on healthy trees literally explode when high heat is applied. Just like a chemical incendiary bomb, these oils, resins and other flammables create fire storms as the trees disintegrate sending branches, firebrands and firestorms high into the air. Once started these chemicals fires create the crown-jumping scenarios that are the most destructive elements of a wildfire. Extreme fires can emerge out of a forest fire whose heavy fuel loads along with abiding winds coax out a crown fire. There are three types of crown fires: Passive crown fires are those in which trees torch as individuals, ignited by the surface fire. These fires spread at essentially the same rate as surface fires. Trees torch within a few seconds with the entire crown enveloped in flames from its base to the top. Active crown fires are those in which a solid flame develops in the crowns. The surface and crown fires advance as a single unit dependent upon each other. Independent crown fires advance in the crowns alone, independently of the behavior of the surface fire. Once a crown fire gets rolling, it can evolve into a full-fledged fire storm. The physics defining such behavior occupies its own special category. A fire storm is a class of extreme fire behavior, and is defined as violent convective columns caused by large continuous areas of fire, often appearing as tornado-like fire whirls. They can also occur from uneven terrain as fire spreads through an area. Acting like a circle of bellows, a fire storm sucks in air from a prescribed spherical radius, feeding the fire which begins to burn at abnormally high temperatures as concentrated in a confined area, and in sending a pyro-cumulonimbus cloud skyward several thousand feet in effect creates its own weather pattern. This kind of mass fire is capable of generating its own wind fields associated with the massive thermal up-drafts of air. Such a conflagration develops “great balls” or whirls of fire which advance along the top of the forest canopy and like a Gaucho releasing a bola as spun above his head will toss fire brands ahead of the main fire great distances. After falling to earth spot fires can be created. The fire spreads faster than it would otherwise. There is reason to believe that fires across the West burn hotter and more fiercely now than in the past before extensive logging occurred. Accounts of early surveyors explicitly state that crown fires were uncommon. In 1899, when George Sudworth was surveying the central Sierra Nevada, fires were so routinely encountered that “travel through a large part of the territory was at times difficult on account of dense smoke” (Sudworth1900, p. 560). Nevertheless, Sudworth states of these, and previous fires: “Fires of the present time are peculiarly of a surface nature, and with rare exception there is no reason to believe that any other type of fire has occurred here.” (Sudworth1900, P. 557) “The incidences in this region where large timber has been killed outright by surface fires are comparatively rare. Two cases only were found. . . . One of these burns involved less than an acre, and the other included several hundred acres.” (Sudworth 1900, P. 558) Simply put, wild fires are becoming more dangerous and more difficult to suppress. As fire suppression policy and techniques have been refined, the United States loses much less acreage to wild fire than one hundred years ago, but the costs are much higher as are the losses of human property and lives. Across the American West fast moving fires exhibiting extreme behavior are increasing phenomena. Before the late 1980s, the typical spread rate for a fire was about a chain (66 feet or 20 meters) per hour. Now, major fires, such as Southern California's 273,000-acre Cedar fire and the 108,000-acre Simi fire, spread at a rate 20 to 50 times faster than that. Some consume more than 100,000 acres per day. In almost every case, wildland/urban interface issues come into play. Reservoirs, communications towers, and communities encroach on wildlands so that in almost every fire incident, management teams are dealing with a community at risk. Recent interface wild fires include: the frightening Cerro Grande fire in Los Alamos, New Mexico(2000 - 47,000 acres) Southern California’s Big Bear Lake’s “Old Fire” (2003- 91,300 acres), and the Martis Fire (2005- 25,000 acres) in the nearby Mount Rose Wilderness north of Tahoe that came within seven miles of Reno. Tahoe South Shore’s Gondola Fire (2002) has been the most recent of high threat forest fires in the basin itself. All these fires and more have served stern notice to Tahoans. Residents in the basin now live in perpetual fear knowing that a conflagration could await them. Unless the forests can be managed properly and soon, it is not a question of if but when. It has become a race against time as fire agencies work to reduce fuel loads around the basin. Even newer techniques of fire prevention carry risk. Controlled burns- also known as prescribed fires- are becoming feared as well. The Los Alamos Cerro Grande fire started out as a prescribed fire that eventually burned out of control. It charred over two hundred homes and apartment buildings in Los Alamos itself, approached within two hundred fifty meters of the town center, and came very close to consuming Los Alamos’ nuclear weapons production and waste storage facilities at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) which was shut down and evacuated. What deadly materials could have been released from the nation’s foremost nuclear research center if it were to have been destroyed by fire can only be imagined. The United States as a whole is experiencing an epidemic of tree-killing insects, droughts and wild fires. Global warming is believed to be a major culprit. The current global climate change may or may not be attributable to “global warming” as created by man, but it doesn’t much matter the reason. Rapid warming over the last thirty years has resulted in a growing fire threat, no matter the root cause. As a child growing up at beautiful Lake Tahoe in the 1960’s I was blithely ignorant of the nexus of salient scientific and historical facts that inextricably bound the deteriorating conditions of Sierra Nevada forests, lakes, and rivers to the discovery of gold and silver in Virginia City, the arrival of European-Americans to the Tahoe Basin, and the displacement of the Washoe Indians. I simply stood on the pure white sands on the beach frontage of my parent’s hotel in Tahoe Vista, looked out at the great blue waters of the lake and admired the surrounding basin forests- most of which were second growth and bore no resemblance to their virgin ancestors. The Washoe had been gentle and competent stewards of the greater Tahoe-Carson area for maybe ten thousand years. They lived according to the almost universal credo of Native Americans who despite there many cultural difference all seemed to agree that “the Earth does not belong to man- man belongs to the Earth.” It is evident that such a philosophy- however best for nature and man as well- is powerless in keeping the destructive hands of pillagers at bay. Men who mistake precious minerals for wealth are bound to destroy the real wealth at hand. The current generation of local people- whether Native American or European-American in descent (or any other extraction for that matter), have inherited both a bounty of natural beauty that still survives, but also the terrible environmental imbalances that thoughtless exploitation of natural resources have engendered resulting from the actions of only one generation of men a hundred and fifty years. Fire, fire, fire. As there are fires in the hearts of men, there will be fire in the mines, and fires in the forest. How little the Comstock Lode gold and silver miners understood- or probably cared- what their ultimate legacy would be. And accompanying these manmade fires, there always seems to be water nearby- but the flooded mines never stamped out the fiery explosions from combustive gases set alight from their depths and the deep blue waters of Lake Tahoe can’t be collected in a vessel large enough to douse a firestorm ablaze in the basin just a stone’s throw from the lake’s shore. Water is never enough to quench a man’s thirst or douse the burning heart of a fire. A miner’s first choice is fire water- not water itself. As for the fire in a man’s heart, it consumes first the world around him, and then finally himself.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()